Pimp-Pimp Hooray!

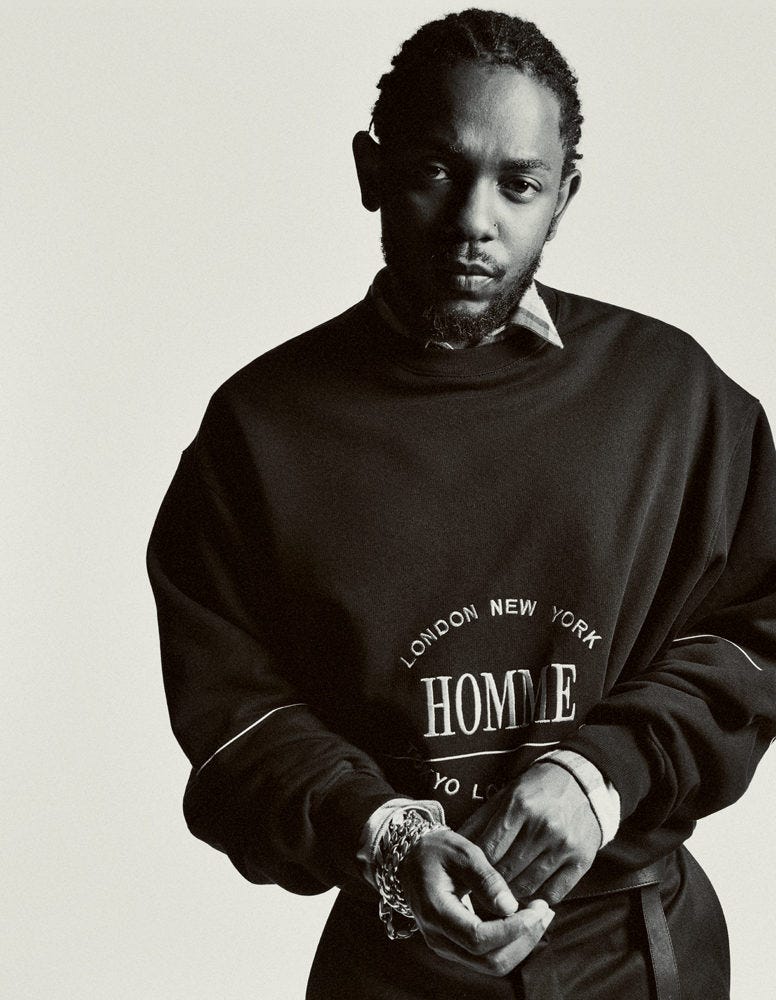

Kendrick Lamar develops a storyline with all the hallmarks of classic storytelling: exposition, rising tension, a pivotal climax, and resolution—plus a colorful cast of adversaries.

Interlude: Jazz

On September 15, 1963, a church in Birmingham, Alabama, was the victim of an attack perpetrated by four members of the Ku Klux Klan. When the dynamite sticks placed under the church floor exploded, the blaze took the lives of four young black girls and injured twenty-two other people. In a state considered one of the most racist in the country, the attack was described by Martin Luther King as the manifestation of the worst vices of humanity. He gave a two-part speech three days later at the girls’ funeral, first paying tribute to them, then insisting on the need to rise up and continue fighting racism in all its forms.

Two months later, accompanied by Jimmy Garrison on bass, Elvin Jones on drums, and McCoy Tyner on piano, saxophonist John Coltrane entered the studio.

The group recorded the track “Alabama,” released on the album Live at Birdland in October 1963. The tempo and atmosphere of the song are modeled on Pastor King’s speech: somber at first, as the faces of the young girls seep into the minds of those present at their funeral, then brighter, as the hope that the days might lighten overtakes the horror.

Coltrane proves once again that jazz is an art that, while sometimes wordless, can say things, advocate, and sublimate distress. Be-bop and free jazz, two complex stylistic currents full of pride and spirituality and free from any thematic constraints, have shown that the possibilities of expression are endless: all that remains is to play, to manhandle drums, pianos, and basses, to play, to improvise until out of breath.

“Music must sometimes terrify,” says Archie Shepp, an icon of free jazz and the Afrocentric movements of the sixties and seventies, whose album Attica Blues was composed in memory of the Attica prison riot in 1971. “It must shake men by the throats. It must extol the inevitable triumph of full stomachs and fat laughing babies. It must bring social as well as aesthetic order to our lives. If it is not enough simply to play it then we must state the fact unflinchingly: This much is true America: A man ain't nothin’ but a man.”

Max Roach sat on this ugliness in 1960, with the five tracks composing his album We Insist! Max Roach’s Freedom Now Suite, five militant pieces evoking racism and slavery. In his book Sounds of Surprise, jazz in 100 records, Franck Médioni recalls that Max Roach declared upon the release of his album: “I will never again play anything that does not have social significance. We American jazz musicians of African descent have proved beyond all doubt that we’re master musicians of our instruments. Now what we have to do is employ our skill to tell the dramatic story of our people and what we’ve been through.”

It was then an echo, more than fifty years ago, of the position adopted by Kendrick on To Pimp a Butterfly, where the rapper also denounces racism, oppression, and the internal conflicts against which people struggle. Using a lot of jazz, as a vehicle for his thought.

Jazz-Hop

Kendrick didn’t grow up with jazz: his parents preferred the frenetic rhythms of soul and funk. In the Chicago of the seventies and the Compton of the eighties, jazz harmonies didn’t find their place; Kenny and Paula had heard of John Coltrane and his struggles but didn’t buy his records. And so, Kendrick didn’t rub shoulders with it. At least, not voluntarily.

This music wafts behind the work of artists alongside whom he grew up: that of the Native Tongues, Digable Planets, D’Angelo, Erykah Badu, Pete Rock, and De La Soul. While he never leaves the borders of Los Angeles, this music is distant, far from the works of 2Pac and Tha Dogg Pound, and he only discovers it later, as he allows himself to explore other discourses and styles. Despite this, many of the instrumentals on which he lays his voice, and this from the Kendrick Lamar EP in 2009—on the track “Celebration,” with its brass borrowed from Roy Ayers—have a strong jazz flavor. He admits on The Fader:

“I don’t even think that I actually did before. I’ll tell you this: the majority of the beat selections that I was picking early on in my career was all jazz-influenced, but I never knew. I just knew I loved these melodic sounds and these different notes, until somebody had to pull me to the side and say, ‘These are all jazz-influenced records, the sounds that you pick. This is what you like, this is what you love, this is why you like it.’”

Jazz serves as a foundation for him to lay his voice, he uses it as a discreet plan when he addresses the listener directly and speaks closely to ensure they listen. On “The Heart Pt. 2,” the first track of Overly Dedicated, he thus recalls as if he were in front of the microphone of a jazz club, where the silhouettes of musicians blend into the blurs from the cigarette smoke of the spectators; a hushed atmosphere is sketched, enhanced by a drum that underlines his voice, which gains intensity without ever rising above the instrumental, as if jazz could contain his anger.

On “Night of the Living Junkies,” and “Opposite Attract,” a production by Willie B, the piano frames stories of youth and love told from opposing perspectives, while on “Heaven and Hell,” Swedish producer Tommy Black does a new appeal to jazz allows Kendrick to list the poisons contaminating his existence.

On Section.80, Kendrick pursued his exploration of jazz, on “Rigamortis,” and especially on “Ab-Souls Outro,” the penultimate song of the album, produced by Terrace Martin, which closely resembles a jam session.

“I am a human muthafuckin’ being over dope ass instrumentation/Now fuck ‘em up, Terrace!” asks Kendrick, giving the producer permission to blow free jazz, in a frenzy of chaotic rhythms. The touches of jazz in Section.80 catch the attention of Pharrell Williams: on tour in Japan, he listens to “Hol’ Up” and “Rigamortis” on repeat. He is captivated by Kendrick’s ability to layer hard lyrics over jazzy instrumentals. Truly, he is convinced that the rapper is the next big star of American rap, appreciating his willingness to make the music he wants without worrying about targeting a specific audience.

good kid, m.A.A.d city, apart from the sample of “Maybe Tomorrow” by Grant Green on “Sing About Me, I’m Dying of Thirst,” logically borrows little from jazz: a narrative of Kendrick Lamar’s childhood and adolescence, who at the time was not interested in the music of Coltrane or Miles Davis, preferring to get dizzy to the sound of Young Jeezy when he embarked on a ride with his buddies (“The Art of Peer Pressure”).

It was not until To Pimp a Butterfly in 2015 and untitled unmastered. the following year, that jazz once again occupied a prominent place in Kendrick Lamar’s work. While rap and jazz have never ceased to blend, rarely have they achieved such synergy and, above all, such a level of media exposure.

Nothing is calculated in advance; everything emanates from sensations and feelings, as musicians improvise for hours without knowing what their next note will sound like. Terrace Martin also affirms that participating in the recording of To Pimp a Butterfly is like playing in a jazz club with other musicians who learn to talk to each other with their instruments, without uttering a word.

On these two albums, Kendrick raps not to go crazy, he embodies the experience of the black man in America, his troubles and challenges, his small victories and great battles, as, before him, Miles Davis, Lonnie Liston Smith, Art Blakey, Charles Mingus, Sun Ra, Cecil Taylor, or Archie Shepp played it, as Coltrane had blown it, as Max Roach had hammered it.

Lost in the midst of an identity crisis, Kendrick digs into his roots and into the depths of black American music to divert sounds and sublimate them, to give vigor back to music that no longer occupies the front rows in an industry that has changed. Without really thinking about it, he was going to put jazz back at the center of the equation.

Kamasi

In 2014, jazz is one of the genres that sells the fewest records in the United States, according to the annual Nielsen Music report. It suffers from a dowdy, outdated image, carries the unglorious reputation of a music from another time, no longer in tune with the tastes of the new generation of listeners, those who have made rap one of the best-selling genres in the country.

To Pimp a Butterfly reverses the trend. Symbolically, at least. The Epic, Kamasi Washington’s project, the saxophonist who plays a central role on Kendrick Lamar’s album, would it have had the same impact if To Pimp a Butterfly had not known such critical and commercial success? It is certain that it offered new exposure to all the musicians who illustrated it. They listened to the same artists as Kendrick, fed on the same influences but made them flourish in different directions.

Most of them gathered in Leimert Park, a neighborhood near downtown Los Angeles, a hotspot for the jazz scene and black American culture. Kamasi Washington, Thundercat, Ronald Bruner Jr, Ryan Porter, Miles Mosley, and Terrace Martin, great artisans of To Pimp a Butterfly, play together in Leimert Park in the rooms of the World Stage and the 5th Street Dick’s.

All are part of or gravitate around the West Coast Get Down collective, formed to bring together the forces of the Los Angeles jazz scene and celebrate its rich history.

Between 1920 and the end of the fifties, on Central Avenue in the city, the cream of the country’s music scene met to play and dance in jazz clubs. The avenue hosted Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Eric Dolphy, Charles Mingus, Ornette Coleman, Lester Young, and many others: all contributed to making this place one of the bastions of jazz in the United States. Stretching over about ten kilometers, Central Avenue runs through Compton, Watts, and Carson, passing by Kendrick Lamar’s house, his high school, the city where Top Dawg built his studio, and the Nickerson Gardens.

At the end of the fifties, the clubs closed one after the other, affected by the economic crisis following the disappearance of factories and under the pressure of Daryl Gates, chief of the LAPD, who viewed the racial mixing of concert halls, where blacks and whites gathered for an evening, with disapproval. When Kenny and Paula Duckworth settled in Compton, the vibrant scene of Central Avenue was therefore just a memory, but in the space of forty years, well before electro or rap took its place, jazz became anchored in the DNA of Los Angeles, influencing the musicians of Kendrick Lamar’s generation.

“Here, in Leimert Park, we play our jazz, the music we grew up with, for Black people, not for the rich. And they love it. It’s jazz for the ghetto,” proudly states Kamasi Washington.

“We all went to the Project Blowed room hoping to see guys like the Freestyle Fellowship or the Alkaholiks freestyle. We were there, with all the hip-hop fans, and then we went home to transcribe all that thinking about Charlie Parker. Everything coexisted. There is a very clear and apparent connection between jazz and rap,” adds the saxophonist, who cut his teeth, like members of the West Coast Get Down, within the Snoopadelics, Snoop Dogg’s touring band.

Playing in Snoop’s brass section allows Kamasi to develop two visions, that of rap and that of jazz. On To Pimp a Butterfly—yes, in addition to playing the saxophone, he is also responsible for the string section arrangements—he thus manages to position himself constantly at the border between the two genres, sharing Kendrick Lamar’s musical heritage and striving to infuse it with a touch of his own sensitivities.

In the studio, he writes scores, works on melodies, and Kendrick asks him questions, tries to understand why he plays such a melody on the piano and what it will sound like when interpreted by another instrument. As the instrumentals are built, he already tries to see how he can lay his verses on them, how to modulate his voice and flow to adapt to the musicians’ work.

On TPAB, Kamasi’s saxophone is a hyphen that ties the whole project together. It’s he who unleashes the madness of “u,” he who blows the revolution on “Alright,” he who seems to recite the poem of “Mortal Man,” the first track that Kendrick Lamar made him listen to, and which serves as the basis for all the songs on the album. It’s also he whom we hear first timidly, then more frankly on “For Free.”

And it’s this track that best summarizes Kendrick Lamar’s relationship with jazz.

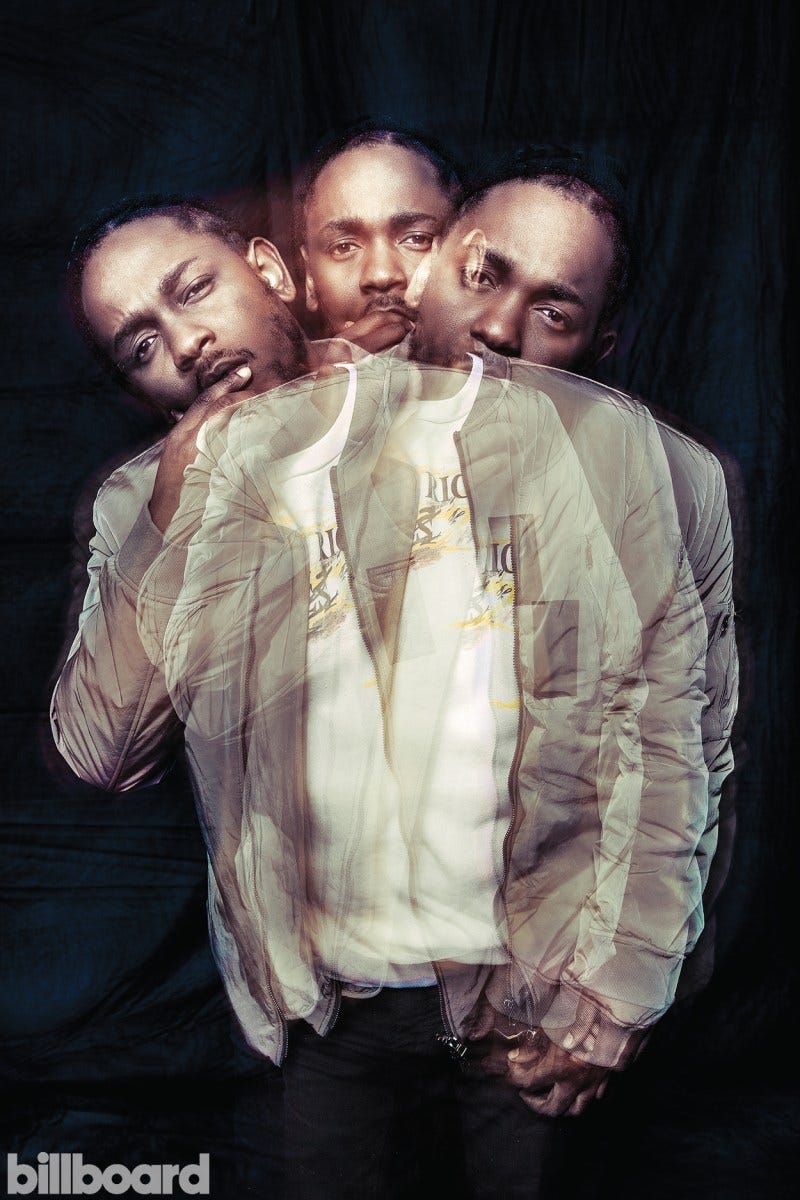

Jazzman Rather Than MC?

There is first its video, where Kamasi Washington and Thundercat appear with their instruments, then where a frantic chase unfolds between Kendrick Lamar and the vices trying to make him fall into Hell: money, sex, racism, Uncle Sam. Caricatures of black women and men appear briefly, subliminal images overlap, snake shapes and strange statues stand in his way.

He runs to escape them, hides, duplicates himself to flee temptations. He surrenders to a chaos of rhythms, lost in a world created by brilliant free jazz, where choirs, saxophones, and drums respond to each other. The whole forms a mastered cacophony that has almost nothing to do with hip-hop, and everything to do with jazz.

And then, there is Kendrick’s flow and voice, which, more than on any other track in his career, mimic the sound an instrument would make. The rapper and his instrumentalists dialogue, accelerate their notes and deliveries, emphasize words to highlight tones, while percussions and strings increase in intensity.

Kendrick works closely with pianist Robert Glasper to build “For Free.” He asks him to play certain notes to accompany his flow, especially for the second part of the song, the most technical. Robert Glasper decides to consider the rapper’s voice as an instrument that his piano must embellish.

“He sounds like several instruments to me. I really think that sometimes he sounds like a trumpet or a saxophone. Just in the way he articulates his cadence. It’s really crazy,” analyzes Glasper.

The latter initially hesitates to do what Kendrick asks him because he fears that his notes might erase the rapper’s presence. But the latter reassures him and asks him again to play not as if he were on a rap track but indeed as if it were a jazz song.

As a result, when Kamasi Washington hears the drafts of “For Free,” he immediately thinks that Kendrick is a jazz enthusiast and has been studying this music for years. He also imagines that in addition to rapping, he is a bassist or trumpeter, amazed by the rhythms he manages to create with his voice. Terrace Martin tells him that this is not the case, and that Kendrick has just listened to A Love Supreme by John Coltrane for the first time, an album that, due to its spiritual anchoring and poetic aspect—it is structured around a poem written to God, while To Pimp a Butterfly is built like a poem that Kendrick reads to 2Pac—shares many aspects with To Pimp a Butterfly.

“The whole album needs to sound like it’s on fire,” Kendrick once said about TPAB, after listening to Coltrane, understanding that the saxophonist's music is both elegant and rooted in the reality of the civil rights movement of the sixties, as soft as it is abrasive, the expression of a man who, with the strength of his saxophone, paints a world that is no longer turning right.

Thus, the discovery of A Love Supreme changes his approach to music. He also spends long hours listening to Giant Steps or My Favorite Things, two other works by Coltrane. For Terrace Martin, the lineage with John Coltrane is logical:

“He is the John Coltrane of hip-hop right now,” he asserts, before emphasizing that both are discreet, shy, and, above all, workaholics who constantly seek to perfect their art. “I played that [A Love Supreme] for him for a reason. For one, that’s not the record you introduce someone to [jazz] with. But I did that because he’s so advanced. I told him on a text—this record we’re doing right now [To Pimp a Butterfly], this feels like your fourth or fifth record. It feels like your A Love Supreme. Like when Coltrane came to grips with the true spirituality part, and started giving up the horn technicalities and became deeply into the spiritual aspect, just getting really into improvising. I feel like Kendrick does this in his music.”

On To Pimp a Butterfly, it’s not about sampling jazz records, as DJ Premier, Q-Tip, or Pete Rock might have done, but about creating something entirely new, by collaborating with artists who are given total creative freedom. Apart from Rapsody—and a Snoop Dogg who doesn’t really rap—no rapper is present on the album: the guests are jazzmen, to the point that it’s sometimes difficult to determine whether it’s a rap or jazz album, with the boundaries constantly blurred. Interviewed by journalist and author Marcus J. Moore, Robert Glasper confirms:

“Kendrick has a lot of respect for everyone. He speaks to jazz enthusiasts, music geeks, those who listen to old school rap, and gangsters. It’s ‘real tap crossed with jazz,’ something I was already doing in my world, but when Kendrick did it, it changed everything."

Many of the recording sessions for TPAB are preceded by long periods of listening to jazz, but also funk or soul, with Kendrick wanting to immerse himself again in the music of the sixties and his childhood. In parallel, he watches video tapes of himself when he was very young, dancing at parties organized by Kenny and Paula in Compton. Above all, he listens to the music playing in the background and observes the reactions of those present in the videos. He captures their movements, their smiles, and tries to remember them when he enters the recording booth. He is also inspired by the innocence of the children he sees around him, and that of his niece, who was two years old at the time of recording the album. He is fascinated by her ability, and that of other kids her age, to see the world without fear, to know nothing of the reality in which Kendrick must navigate every day.

Terrace Martin regularly sends Kendrick ideas for melodies hummed on his iPhone, which they then reproduce in the studio to form the bases of the album’s songs. And when the rapper is finally ready to lay down his voice, it’s often Terrace who stands by his side and gives him advice.

Terrace Martin, a native of Los Angeles, represents the golden generation of the city’s musicians and, since 2007, has accompanied most of Top Dawg Entertainment’s releases. He is the unacknowledged architect, the one who is not always credited, wrongly, as one of the label’s founding members.

Without his eclecticism, neither Kendrick Lamar nor TDE would have succeeded in developing their sound in the same way.

The Homie Terrace

Terrace doesn’t like to talk about himself and prefers to stay in the shadows.

On the covers of his projects Velvet Portraits and Sounds of Crenshaw, Vol. 1, you don’t see his face, but rather images of his city, Los Angeles. His entire career is tied to it and draws inspiration from it.

Velvet Portraits, which he recorded in parallel with his work on To Pimp a Butterfly, reflects the ever-evolving music scene of L.A., capable of sublimating rap with a touch of saxophone, and bringing jazz back to the street, using a snare drum to nail it to the asphalt. It’s revealing to listen to Terrace’s take on Kendrick’s “Mortal Man,” softening it to the extreme, adding violins, pianos, and brass to transform it into a sentimental ballad.

Because everything is about reinvention with Terrace Martin: after being immersed in rap during his childhood, he succumbs to the calls of jazz.

At the feet of his father, a jazz drummer, who introduces him to the musical heritage of his time. Terrace falls in love with the sound of the saxophone while listening to A Tribe Called Quest, but it’s his father who introduces him to all the artists who inspired Q-Tip and his crew. Nine years older than Kendrick, he also experienced the gang wars that ravaged Los Angeles in the eighties and nineties, and, like K-Dot during his adolescence, considered the gangster life as one of his only alternatives. The same gangsters he admired were lulled by the funk of Roger Troutman and his talk box, which had helped shape g-funk.

Like Kendrick, again, he dissected the sound of N.W.A, Del the Funky Homosapien, and Too $hort, but mixed it, unlike the Compton cosmology, with Grover Washington Jr., Phil Bowles, Herbie Hancock, and even Beethoven and Bach.

Thus, when he starts working with the TDE team from 2006, two years after the label’s creation, and following a brief experience with P. Diddy and numerous collaborations with Snoop Dogg and his group 213, he brings all these influences with him and shows Sounwave how to assemble them while maintaining a hip-hop identity.

With Family

Martin benefited from the advice of two artists who play a considerable role in Kendrick Lamar’s career: DJ Quik and Dr. Dre. Beyond Quik, he learns how to get the most out of his instruments, while Dre teaches him discipline and shows him how hard he will have to work to achieve his goals.

His first collaboration with TDE is with Jay Rock and K-Dot in 2007, on “Tell Yo Momma,” inspired by “Wait (The Whisper Song)” by the Ying Yang Twins, on which it is difficult to detect Martin’s touch. Immediately, Punch and Top Dawg knight him and he starts hanging out regularly at the Carson studio.

He develops a chemistry with Kendrick, which is evident from Section.80, then on all of the rapper’s albums. He explains:

“I’m very close to Kendrick and Jay Rock because we all started together. We made money with music for the first time, all three of us. I was always playing in jazz clubs and so I put jazz on the beats, and in return, I appreciated the poetry they infused into my music.”

The relationship between Kendrick and Terrace is based on trust, and that’s why the rapper entrusts his counterpart with recruiting the artists he wants to design the backbone of To Pimp a Butterfly.

Terrace invites the singer Lalah Hathaway, daughter of Donny, a soul legend artist, to lend her voice to a few tracks. The recording is quick: the story of two thirty-minute sessions each, in Dr. Dre’s studios in Los Angeles. Lalah appears three times on the album, on “Momma,” “Complexion (A Zulu Love),” and “The Blacker the Berry.”

It’s also him who recruits Larrance Dopson, co-founder of the super-producer group 1500 or Nothin’, and whose percussions structure the project. Terrace also relies on a family member, his cousin Thundercat, whose bass is one of the central elements of TPAB. It serves as the basis for Kendrick Lamar to write “i”: he draws inspiration from it, writes around it; it’s also what gives all its flavor to “King Kunta” and blows the funk, what gives birth to “Complexion (A Zulu Love).” It’s what, finally, brings fluidity to “FEEL.,” an excerpt from DAMN., and allows the song to maintain an almost lazy, smoky aspect, as if lost in an alternate universe where voices would be terribly distant and feelings, terribly sad.

Like Terrace Martin, Thundercat introduces Kendrick Lamar to his favorite jazz albums. He plays him Ron Carter, Mary Lou Williams, Herbie Hancock, and Miles Davis. In the studio, he once plays Kendrick what he’s working on in parallel, notably a song he composed with Sa-Ra. Upon hearing it, Kendrick immediately asks him to introduce him to the bassist who shines on it, laying the foundations for a collaboration with Taz Arnold, who appears three times on To Pimp a Butterfly.

Terrace Martin also recruits the trumpeter Ambrose Akinmusire, whom he has known since the age of sixteen.

“Terrace is one of the only guys who really knows jazz and hip-hop, and knows how to bring the two worlds together,” Ambrose asserts about Martin.

It is for this reason that he feels so at ease with “Alright,” seamlessly partnering with someone to complete the work of Pharrell, or that Sounwave calls on him with “Hood Politics,” asking him, after presenting the instrumental, to add what he deems pertinent. It’s also for this reason that each time he invites Kendrick Lamar on one of his personal projects—on “Triangle Ship,” “Thirsty,” and “I Had No Idea,” where Kendrick delivers a high-quality verse—the alchemy is optimal.

His collaborations with the artists of TDE are numerous: he participates on Blank Face LP by ScHoolboy Q, on These Days by Ab-Soul, but also on good kid, m.A.A.d city, where he illustrates on the first part, with lightness, of “The Art of Peer Pressure.”

“Sounwave, Kendrick, and I really have a ‘thing’ when we work together, which makes me progress. They think outside the box, like me, and so we always create original things. [...] My goal is to elevate people’s spirits and allow them to forget the hard blows,” summarizes Terrace Martin.

Making music allows “to forget the hard blows”: the mantra of Terrace Martin has become that of Kendrick Lamar, since the release of the Kendrick Lamar EP, on New Years Eve 2009.

A project that allows him to understand what artist he wants to become.

A Butterfly Story

“Back when I was listening to the song ‘The Payback’ [by James Brown], I had a bad feeling about some of my past memories. I was depressed. I wanted to sleep, to dream, to escape. I didn’t want to die without having brought something significant, something meaningful to the culture. But who? Where did it come from?”

As he states in “The Heart Pt. 3,” the world sees him as a “2Pac reincarnated.” Kendrick excels at making the rapper: he allows him to relive the time of an album, titled To Pimp a Butterfly.

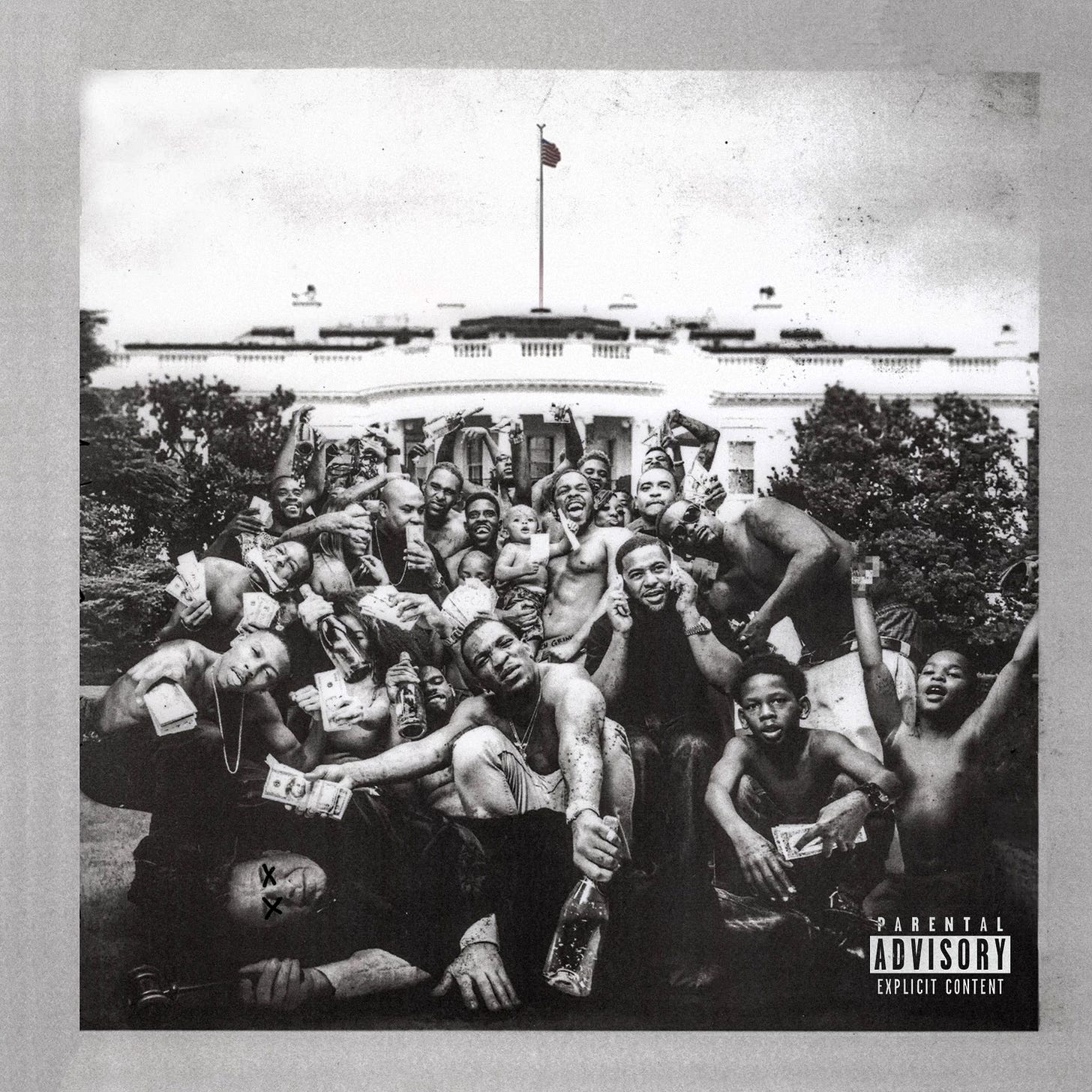

The name completes the project revealed in the booklet that accompanies it, with the words written in braille: To Pimp a Butterfly, A Blank Letter By Kendrick Lamar/Prostitute-Customizer referring to Harper Lee’s novel To Kill a Mockingbird, a story unfolding in Alabama in the 1930s, at a time when racial segregation was affecting all layers of the South in the United States.

It’s clear that Kendrick parks next to To Pimp a Butterfly, a butterfly: one letter stands out among Kendrick Lamar’s customers—a reference to the novel by Harper Lee, To Kill a Mockingbird, a story set in Alabama in the 1930s, during a time of racial segregation in the United States.

“We know the story of Tom Robinson, a Black man accused of a crime he did not commit, forced to endure the system’s injustice, just like the character of the surviving criminal in the accusation. To some extent, these tests are similar to those Kendrick Lamar faces on the album: from now on, the famous rapper must face the consequences of his successes without losing sight of his roots and the role of the leader that the public attributes to him, despite the rap of his explanation and reason:

‘The famous “prostitute” is so aggressive, putting the butterfly in the spotlight that I could have been, so much so that I can see myself using this fame for good. Another reason is that I don’t want to let the industry prostitute my fame.’”

Twenty years after Me Against the World, the album where 2Pac became more introspective—announced for March 22, 2015—To Pimp a Butterfly finally came out a week earlier due to racial segregation that had affected all layers of the South in the United States.

2Pac was obviously even more prescient than Shakur, Kendrick decided a few weeks before the album’s release to change the word “caterpillar” to “butterfly.” The rapper wanted to avoid any return to his model accumulated during the measure of time around a poem that he wrote for 2Pac.

Because it’s obvious that Kendrick shares much with TPAB, he’ll confirm his doubts and share his shadow, for a few successes and small victories. It’s to 2Pac that he addresses, because no other person can understand, for the simple and good reason that Shakur went through these trials.

To continue “Mortal Man,” Kendrick held an interview in Sweden with a reporter during a trip to Mats Nileskär, a journalist from the center. The interview took place in 1994 at Quad Recording Studios in New York, where he had been shot five times and robbed for $40 million worth of jewelry. During a break from the interview, Kendrick Lamar, now focused, spoke for hours, hoping that he would recover completely in the studio while working.

Sincere genius of his son, his musician, choir, dancer, boxer, his family or friends, justice, an ordinary man and a table of mixes, Songs premiere person, son of the mother of Tupac, who gave him the authorization to use the voice of her son, Kendrick decides to rearrange the interview with breaks in his voice, so it sounds like a discussion he could have had with Pac, placing this section at the end of his album.

The whole thing is overwhelming; Kendrick is almost overcome by the man he’s supposed to face. “I got the impression that someone I identified with, who I could have been, left me after you left one day,” he says to Simon, continuing, “I finally had the chance to speak...”

Kendrick Lamar notably asks him to share his vision of society, thinking that what he says might help him face what’s happening in 2015 in the United States. He also asks how he managed to stay sane in an environment where everything seemed to lead to madness.

“By my faith in God [...] and by the certainty that good things happen to those who stay true,” 2Pac simply responds.

The rapper also describes how he managed to become a millionaire by sharing nothing, how he ended up having a dominant relationship, and how this meant becoming an entrepreneur in the United States; on top of that, taking the title of To Pimp a Butterfly, how he managed to get out of his shell to transform into a butterfly, free to go where he wanted.

2Pac gives some advice to his young disciple:

“In USA, a Black man only have like five years we can exhibit maximum strength, and that’s right now while you a teenager, while you still strong, while you still wanna lift weights, while you still wanna shoot back. ‘Cause once you turn 30, it’s like they take the heart and soul out of a man, out of a black man, in this country. And you don’t wanna fight no more.’”

Black Lives Matter

In 2013, Kendrick Lamar had never before mentioned the subject of racism in his work, at least not so directly. But on July 13, 2013, after George Zimmerman was acquitted for the murder of Trayvon Martin, a young unarmed Black man, the Black Lives Matter movement was born. On February 26 of the previous year, the BLM movement had taken shape: three women activists—Patrisse Cullors, Alicia Garza, and Opal Tometi—founded the BLM Global Network Foundation, which, among other protest operations, has since organized demonstrations all over the country in response to the systemic murders of African Americans by police forces and vigilantes.

At the end of that same year, 2014, D’Angelo returned after a decade of absence with a brand-new album, Black Messiah, imbued from the start with protest messages, but in a subtle manner, something more interior and personal than purely political. On that album’s cover, you can see the crowd raising their arms in protest, a powerful image in the fight against oppression. So the return of D’Angelo, an artist from the 1990s, an R&B star who had fallen silent for many years, was greeted as the sign of a new wave, a new impetus, a protest movement that’s about to erupt. That same year, the young Kendrick Lamar emerged.

D’Angelo decided to move up the release date of his Black Messiah by several months in order to release it on December 15, 2014. In it, you can hear “The Charade,” with lyrics referencing the events that shook Ferguson, Missouri. After the deaths of Eric Garner and Michael Brown, multiple protests broke out in 2014–2015 in Los Angeles, San Francisco, Cleveland, Cincinnati, and Washington, D.C., in what seemed like a wave of rejection of injustice.

“If the world were happy, we would have an album titled u instead of i. But it’s not, it’s i, so we must resist,” Sounwave says about the release of To Pimp a Butterfly.

In the middle of the demonstrations with “Alright” on June 19, 2015, two years after the acquittal of Zimmerman, and also the day the track was released as a single, it rose to the status of a “protest song,” with people chanting its chorus and refrain in the streets. Because it’s a track that, in itself, is a protest. Kendrick says so in the lines: “Nigga, and we hate po-po Wanna kill us dead in the street fo sho.” This is also the reason why the track was performed at the BET Awards ceremony a few days later, on June 28, 2015, in a staging that references the case of Rodney King, in 1991. This is the origin of the refrain, “Nigga, we gon’ be alright.”

“All my life I had to fight!”

In the summer of 2015, the Black Lives Matter movement spread across the country, fueled by calls for justice and recognition of the value of black lives. “We gon’ be alright” thus became a rallying cry for many protests, a banner of hope.

As an illustration of what is happening: “All my life I had to fight,” from “Alright.” “A nigga got hurt at the bus stop,” “A nigga got shot by the police,” “Which one of you is gon’ testify? ‘We gon’ be alright.’” A man is killed in the street.

The same scene in Chicago, during a protest against Donald Trump the same year, or in Washington, D.C., at the twentieth anniversary of the Million Man March, people sang “Alright” to voice their anger. By late 2020, the song again emerged, its chorus repeated by protesters, in the wake of the George Floyd tragedy. Over the years, To Pimp a Butterfly has achieved hundreds of millions of streams on Spotify—Kendrick Lamar became the new voice of American protest music. For some, “Alright” is an anthem in the face of adversity. For others, it’s the musical motif of the “New Civil Rights Movement.” Critics and historians debate it.

In Houston, “Alright” was sung at the “Black Women’s Brunch,” organized by the group As We Come Come & See, in the style of gospel. It’s “We gon’ be alright” that resonates among the participants. Critics and music historians analyze it.

At the political level, the Compton City Council, an initiative aiming to recognize the civic engagement of its artists, officially adopted “Alright” as an anthem of protest and resistance.

“The refrain isn’t ‘yeah you go, go, go,’ it’s ‘we gon’ be alright’ in the face of adversity. It’s no longer a personal matter but a communal one,” writes the activist DeRay Mckesson, in an article analyzing the symbolic and cultural impact of “Alright.”

Proof confirmed: “I can’t breathe,” “We gon’ be alright,” “Black Lives Matter,” “Hands up, don’t shoot”—all these slogans converge and respond to one another.

In January 2017, in Washington, D.C., during the Women’s March, “Alright” was again chanted, echoing Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech.

François Moreau on the liner notes, Thundercat the bassist, adds: “Working on the production of To Pimp a Butterfly was like stepping into a bubble, in which we lived and breathed that music. It was the moment for a new wave, something that mixed jazz, soul, funk, rock, rap… We immersed ourselves in Coltrane, Miles, Herbie Hancock, Parliament, The Isley Brothers, Prince, James Brown, Nina Simone, Marvin Gaye, the Beatles, we listened to so much stuff… We tested, tested, tested, and then we tested again. But it was never random. We wanted to achieve a sound that was both raw and refined. Then Terrace Martin brought his jazz influences, Sounwave his trap side, and so on. That’s how we arrived at this unique style. And Kendrick’s words soared on top of it all, reminding us of Martin Luther King or James Baldwin. It was a turning point.”

Recognition came quickly: in May 2015, the rapper was honored with a ceremonial key to the city of Compton, his hometown, for “his positive representation and his philanthropic efforts in the community.”

“‘Alright,’ Kendrick Lamar, and James Brown, Nina Simone, Marvin Gaye… yes, that’s it. The big ones are there,” wrote Barack Obama when he invited Kendrick to the White House. “He is the reflection of our time, the link between a generation and the old guard.”

Compton has never been so close to the Senate.

If “Alright” resonates so strongly in these troubled times, it’s also because the song indirectly references The Color Purple by Alice Walker, published in 1982 and adapted to film by Spielberg in 1985. Indeed, the refrain, “We gon’ be alright,” is repeated like the phrase used by Celie, a Black woman in search of recognition, to gather her strength and survive in a world that seeks to destroy her.

“All my life I had to fight,” declares Celie, the exclamation that Kendrick keeps reiterating for us in Mortal Man, or that he cites in interviews. If The Color Purple is part of his cultural background, then we can guess how its feminist, anti-racist, and activist dimension intersects with Black Lives Matter.

“All my life I had to fight.” The question is, how do you stay strong in the face of adversity, in the face of death, in the face of destruction, in the face of 30 years of a policy designed to crush you, in the face of the dead? What does that mean? What does it look like in 2015? That is what’s at stake.

The parallel with the riots in Baltimore, which erupted about a month before the release of To Pimp a Butterfly, is revealing. In April 2015, Freddie Gray, a young Black man, died from spinal injuries after being arrested by the police. This tragedy sparked massive protests and riots, especially in Baltimore, just an hour from Washington. The National Guard was deployed, curfews were instituted, and the entire city seemed to be on lockdown until the arrest and trial of the six police officers implicated in Freddie Gray’s death. In short, it was nearly an insurrectionary situation. Baltimore hadn’t experienced such tension since the 1968 riots after the assassination of Martin Luther King or those in 1992 following the Rodney King case in Los Angeles.

How do you survive the system when the city is in flames? “When you come from the ghetto, you’re used to a certain precariousness,” says Kurupt, one of the founding members of the G-Funk era. “But we were never prepared for this.”

Nat Turner, In 2015?

Even if the interview of 2Pac presented in “Mortal Man” was recorded in 1994, what Pac said is linked to the events that followed in the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement:

“I think that niggas is tired of grabbin’ shit out the stores. And next time it’s a riot it’s gonna be like, uh, bloodshed, for real. I don’t think America knows it, I think America think we was just playing. [...] It’s gonna be murder, you know what I’m saying?”

The revolt in Saint-Louis was short-lived, but it marks an indication of the extreme tension in which the United States find themselves at the time of the release of To Pimp a Butterfly.

Did you hear it, did you see it? It was like the smell of burning flesh in the air, Nat Turner in 1831! It will happen.

The parallel with the riots in Baltimore, which occurred about a month after the release of To Pimp a Butterfly, is then clear.

On April 12, 2015, Freddie Gray, a twenty-five-year-old Black man, was arrested by the Baltimore police: he was suspected of carrying a knife that he was allegedly forced to swallow. Freddie Gray was brutally neutralized, placed in a van, and arrested, before being taken to the hospital. Gray fell into a coma and died a week later, on April 19, from injuries to his cervical vertebrae. While the police speak of accidental injuries, others suggest violence occurred both at the arrest site and during the van ride. In Baltimore, a city plagued by mass poverty and drug trafficking—especially in the Gilmor Homes complex, near where Gray was arrested—peaceful protests broke out to demand transparency from the police, who provided little information about the victim’s condition during the arrest.

Upon the announcement of Freddie’s death, all hope of calm vanished. Riots erupted, among the most violent in the country.

After the events in Watts in 1992, between April 18th and the 3rd, the city was set ablaze and under curfew; a state of emergency was declared. The mayor, Stephanie Rawlings-Blake, affirmed that “thugs are destroying the city.” The National Guard was deployed, and the figures are alarming: according to the Baltimore Sun, 486 people were arrested, 350 businesses were vandalized, 113 police officers—prime targets of the rioters—were injured, two citizens were shot at, and 150 vehicles were burned.

If there was no “death,” as 2Pac claimed in 1994, the riots were nonetheless one of the key moments of the Black Lives Matter movement. Even though its activists, like President Barack Obama, distanced themselves from this wave of extreme violence.

“2Pac was a prophet to me, and everything he talked about is still relevant today,” recalls Kendrick Lamar.

In Saint Louis, on August 19 of the same year, riots also broke out following the death of Mansur Ball-Bey, killed by a police officer during a search of his home. Invoking self-defense and stating that the victim was armed, the American justice system dropped the charges against the two police officers involved. The situation brings back bad memories for Kendrick, who, at sixteen, witnessed two raids and was himself mistreated by police officers:

“They didn’t care that I was a minor. But they still put their boot in my back and that beam on me. They still did that. It’s just the everyday lifestyle. They still pull you over and put you on they hood no matter how old you are. It’s always been a war, outside of the gang community.”

The revolt in Saint Louis was short-lived but highlighted the extreme tension gripping the United States at the time of the release of To Pimp a Butterfly.

Meanwhile, on a symbolic level and through its messages, Kendrick Lamar has never presented himself as a militant artist. He has always rejected labels, fearing that his music might become confined:

“The ‘conscious’ rap or ‘gangsta rap’ doesn’t exist. If both talk about life, you can’t classify them,” he explains.

To Pimp a Butterfly is, however, the album where he makes the most references to the history and condition of the Black community. He doesn’t address them head-on but rather through metaphors and, at times, literary notions.

In “King Kunta,” one of these helps shed light on his positions.

“What’s the yams?”

“The yams is the power that be/You can smell it when I’m walking down the street,” raps Kendrick Lamar.

Yams—literally: sweet potatoes—are references in slang to two things. The first is the Homme Invisible, for whom you sing? by Ralph Ellison (1952): they return in the experience of a Black man during the post-war period. The work is named after the main character who, although he has invisible skin due to the racist society he lives in, has a voice that can be heard. It is charismatic, a good speaker, he is an intelligent man who takes on the tastes of Americans to occupy a chosen place in a society that wants to keep him invisible, even despised. But as much as he evolves in this environment, he remains unable to change the opinion that people have of him.

On the second verse of “Wesley’s Theory,” the America created by Reagan, who saw in Kendrick and his loved ones individuals uniquely motivated by money, takes the voice of Lucifer to incite the rapper to succumb to all that his childhood and adolescence never offered him. The voice wants to consume and exploit him, because he is a young Black man with success that his destiny has never promised him. Coming from Compton, a city known for its poverty despite being located near Los Angeles, where many rappers are born, Kendrick Lamar remains a kid from the ghetto who will never truly succeed, even if he behaves like the Americans think a young man from the ghettos of Los Angeles should behave.

“When I would sign, my friend, I would do whatever it takes. [...] I wanted to speak for my music. I wanted to do everything for my friends, take them around the world, talk about things that we had never learned in school. They say sometimes that they are ignorant,” adds Kendrick.

And if he succeeded, then he would give a reason to those who would have wanted him to remain in the anonymity of Compton. They would blend in with him and his community, in the depths of success, they would condemn themselves to never be anything more than the collateral damage of a racist policy.

In the second verse of “Wesley’s Theory,” the America created by Reagan, who saw in Kendrick and his loved ones individuals uniquely motivated by money, takes the voice of Lucifer to incite the rapper to succumb to all that his childhood and adolescence never offered him. The voice wants to consume and exploit him, because he is a young black man with success that his destiny has never promised him. Coming from Compton, a city known for its poverty despite being located near Los Angeles, where many rappers are born, Kendrick Lamar remains a kid from the ghetto who will never truly succeed, even if he behaves like the Americans think a young man from the ghettos of Los Angeles should behave.

“And it must be said that they see things, whether it’s Africa, London, or the White House.”

If “King Kunta,” “Wesley’s Theory,” and “Alright” are tinged with optimism, “The Blacker The Berry,” another song from To Pimp a Butterfly, released a month before the album, takes the opposite path and goes to the other extreme in its violent critiques.

The Blacker the Berry

“The Blacker the Berry” is another reference to 2Pac, who declared on “Keep Ya Head Up”: “Some say the blacker the berry, the sweeter the juice.” But while 2Pac recorded “Keep Ya Head Up” to celebrate the beauty of Black women, Kendrick Lamar takes a darker turn: “The blacker the berry, the sweeter the juice / The blacker the berry, the bigger I shoot,” he raps, twisting 2Pac’s words to embody the perspective of a racist police officer. “The Blacker the Berry” carries none of the hope of “Alright,” the progressivism of “i,” or the pride of “King Kunta.” Instead, it is a furious and pessimistic track. Its writing began in 2012, just after the murder of Trayvon Martin, as Kendrick Lamar, on his tour bus, flipped through TV channels and learned that a 17-year-old Black boy had been shot dead.

“It ignited a new rage in me. I remembered what I felt. Being harassed, watching my friends get killed,” he recalls.

Over a Boi-1da beat that abandons the funk and jazz of the rest of the album in favor of jagged rhythms, “The Blacker the Berry” plunges into the hellscape of racism at its most brutal.

“My hair is nappy, my dick is big/My nose is round and wide/You hate me, don’t you?/You hate my people/Your plan is to terminate my culture/You’re fuckin’ evil, I want you to recognize that I’m a proud monkey [...] The plot is bigger than me, it’s generational hatred/It’s genocism, it’s grimy, little justification,” Kendrick raps.

It is also his most controversial, one of the most explicitly confrontational songs of his career. Repeatedly calling himself “the biggest hypocrite of 2015,” he delivers three lines at the song’s close that spark intense debate:

“So why did I weep when Trayvon Martin was in the street?/When gang banging made me kill a nigga blacker than me? Hypocrite!”

Many artists and journalists interpret Kendrick’s words as a critique of the Black community, which “weeps” when one of its own is killed but remains unable to address “Black-on-Black crime”—murders of Black men by other Black men, often tied to gang wars. Critics of the Black Lives Matter movement frequently weaponize this issue to highlight alleged contradictions and divert attention from systemic racism. While Black Lives Matter activists focus on police violence rather than intra-community crime, the topic remains urgent, which is why Kendrick confronts it. He has addressed it since the start of his career: in 2005, he participated in the documentary Bastards of the Party, directed by Cle Sloan¹ and produced by Antoine Fuqua, for which he wrote the song “My People” with Jay Rock. The film explores Sloan’s journey from the Athens Park Bloods to activism aimed at curbing gang violence.

The documentary condemns black-on-black crime, with K-Dot and Rock’s lyrics amplifying its message:

“I refuse to be a statistic, but changin’ my community ain’t realistic/Show me an African American doin’ right, I'll show you one that'll kill his ass tonight [...] We used to run from the KKK/But now we runnin’ from our brothers that be holdin' them ‘K’s/Man, never thought there'd be days like this/Can’t trust your homies that you’re hangin’ with.”

Recent FBI statistics show that in 2015, the year To Pimp a Butterfly was released, Black perpetrators killed 89.3% of Black homicide victims. The issue resurfaced after Nipsey Hussle’s murder in March 2019, shot by a Black man outside his clothing store. It’s also central to Jill Leovy’s acclaimed book Ghettoside (2015), which examines violence in South Central’s Black neighborhoods.

Kendrick’s lyrics on “The Blacker the Berry” align with his 2015 statement to Billboard:

“What happened to Michael Brown should’ve never happened. Never. But when we don’t respect ourselves, how do we expect them to respect us? It starts from within. Not with riots or protests, but within.”

“The dumbest shit I’ve ever heard from a Black man,” rapper Azealia Banks fired back on Twitter. Kid Cudi added: “Dear Black artists, stop belittling the Black community as if you’re a God to all niggas.” Critics accused Kendrick not of addressing Black-on-Black crime but of doing so at an inopportune moment, shifting focus away from urgent issues. Was he unintentionally aiding those who dismiss Black Lives Matter as fleeting? Or is the conservative white America terrified of revolt?

Under fire, Kendrick clarified on NPR: “It’s not me pointing at my community; it’s me pointing at myself.” In a Guardian interview, he went further: “This is in my blood because I’m Trayvon Martin. I’m all those kids.”

At the 2016 Grammys, after performing “Alright,” he paid homage to Trayvon with a new verse, one of his darkest and angriest. He spat out his disgust and bitterness, describing the trauma of Martin’s death and the open wound of American racism:

“February 26th, I lost my life too/It’s like I’m here in a dark dream/Nightmare, hear screams recorded/Say that it sounds distorted but they know who it was/That was me yelling for help when he drowned in his blood/Why didn’t he defend himself? Why couldn’t he throw a punch?/And for our community, do you know what this does?/Add to a trail of hatred/2012 was taped for the world to see/Set us back 400 years/This is modern slavery/The reason why I’m by your house/You threw your briefcase all on the couch/I plan on creeping through your damn door and blowing out/Every piece of your brain ’til your son jumped in your arms/Cut the engine then sped off in the rain [...] HiiiPower, one time, you see it/HiiiPower, two times, you see it/Conversation for the entire nation, this is bigger than us.”

The first-person perspective of “The Blacker the Berry” reflects Kendrick’s own experience as a Black man in America—one who has lost friends to violence, felt rage and vengeance, and nearly perpetuated the cycle himself. His bitterness lingers:

“When Chad was killed, I can’t disregard the emotion of me relapsing and feeling the same anger that I felt when I was 16, 17—when I wanted the next family to hurt because you made my family hurt. Them emotions were still running in me, thinking about him being slain like that. Whether I’m a rap star or not, if I still feel like that, then I’m part of the problem rather than the solution.”

To answer these personal struggles, Kendrick closes To Pimp a Butterfly with a poem on “Mortal Man,” revealing the album’s symbolism: a journey from chaos to peace for himself and his community.

The caterpillar is a prisoner to the streets that conceived it.

Its only job is to eat or consume everything around it.

In order to protect itself from this mad city,

While consuming its environment,

The caterpillar begins to notice ways to survive.

One thing it noticed is how much the world shuns him.

But praises the butterfly.

The butterfly represents the talent, the thoughtfulness.

And the beauty within the caterpillar,

But having a harsh outlook on life,

The caterpillar sees the butterfly as weak.

And figures out a way to pimp it to his own benefits.

Already surrounded by this mad city.

The caterpillar goes to work on the cocoon.

Which institutionalizes him,

He can no longer see past his own thoughts; he’s trapped.

When trapped inside these walls, certain ideas take root, such as

Going home and bringing back new concepts to this mad city.

The result?

Wings begin to emerge, breaking the cycle of feeling stagnant.

Finally free, the butterfly sheds light on situations,

That the caterpillar never considered,

Ending the internal struggle.

Although the butterfly and caterpillar are completely different,

They are one and the same.

After reciting the poem, Kendrick asks Tupac what he thinks of his words but receives no answer. To Pimp a Butterfly ends with an unresolved question, and 2Pac vanishes again after his brief resurrection. Now aware he must use his fame to spread peace, Kendrick reluctantly takes up his idol’s mantle, fulfilling Tupac’s plea from five years earlier: “Don’t let my music die.”

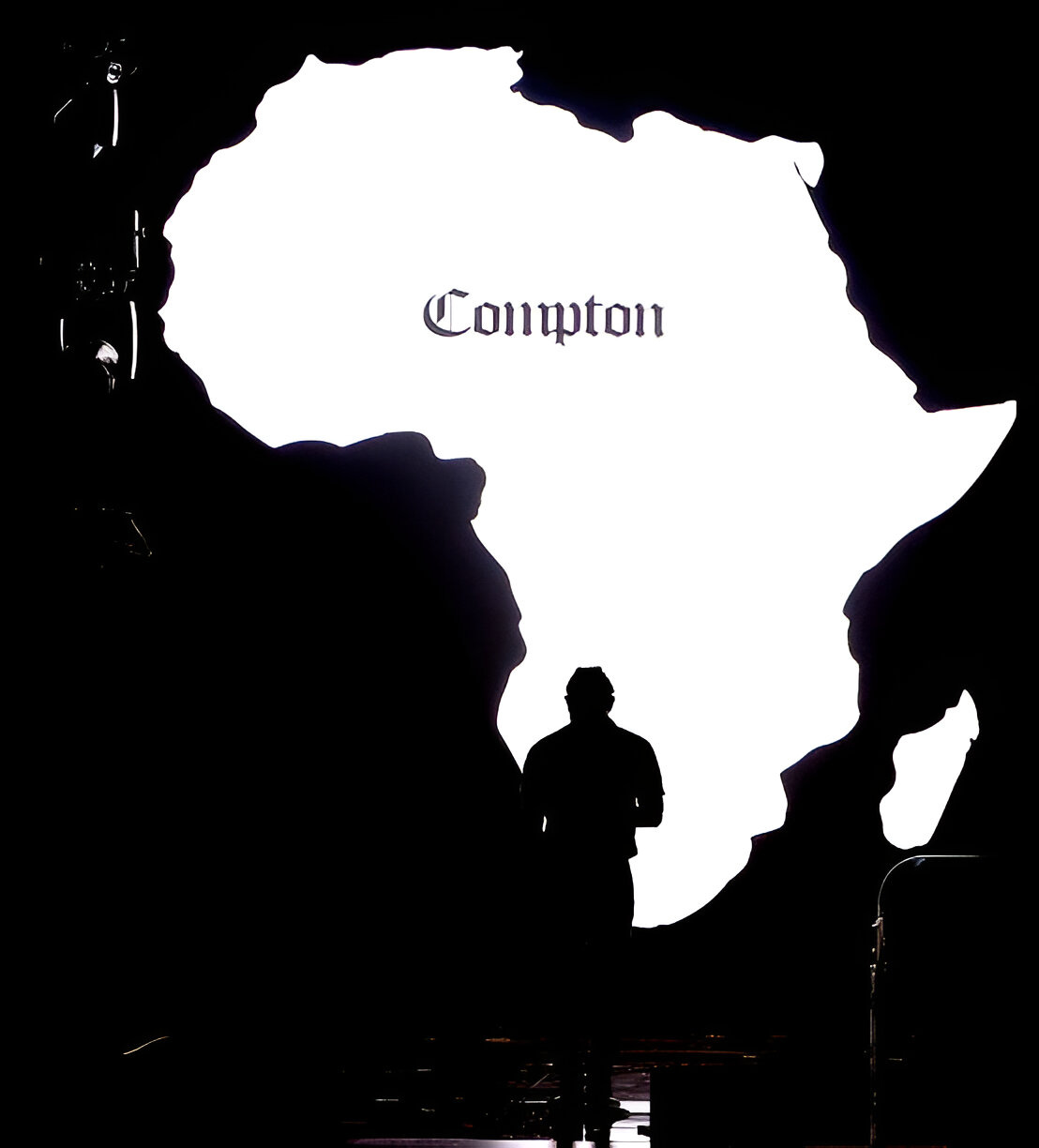

Alone at the helm, the Compton rapper sets his course for Africa.

Momma / Shades of Color

“Free, I suppose, because I had made a decision about my future.”

As soon as Kendrick Lamar set foot in South Africa, he already had the feeling that his journey was only just beginning. In 2014, two years after good kid, m.A.A.d city, there were already African nuances in his music, colors, atmospheres, ambiance.

But in South Africa, everything seems different to him, the colors, the atmospheres, the atmosphere: “It's a place that we, who live in ghettos, never dream of. We never dream of Africa, we don’t say to ourselves ‘Fuck, it’s Mother Earth,’” he admits. But you feel it as soon as you land there. It totally changed the way I convey my art.”

Supposed to last only seven days, the time to do three concerts and leave for the United States, Kendrick would finally explore the cities of Durban, Cape Town, and Johannesburg and soak in the local culture:

South African, on a journey, he wrote a lot, scribbled reconciliations, couplets about buses and taxis, about what he had just experienced. To Pimp a Butterfly, Dave Free often took on the role of a guide:

“What triggers something in his spirit. For me, it’s down there that To Pimp A Butterfly really started.”

It’s a pendant that you wear, the bases of Alright, raised before you in the black South African community in the sometimes harsher conditions than those of his Compton counterparts. It’s also the entire message of the third verse of “Untitled 08 (09-06-2014),” extract from untitled unmastered, where Kendrick recounts this encounter with a rapper from Cape Town, who compared his life to that of the artist:

“And I’m thinking about the youth and the money,” said the poet, “you put your faith in good fortune, you pray for miracles. You’ve never known struggle and you cry like a hysteric. You satisfy yourself no matter what, you complain about everything […] Your ghetto isn’t ridiculous, you live in a hut. I visited you, maintained you, visited to pay my rent. I crossed trials praying to Allah. You’re entertained by going through yours, you dine with Wi-Fi […]. On a boat, all in search of hope. And you, everything you find to say is that you’re looking for drugs. I’m no more compromised than you. The only difference to make, the pain you feel isn’t comparable to mine.”

In contact with the South African population, Kendrick would realize to what extent the Black skin is nuanced, made up of different shades. This revelation pushed him to write “Complexion (A Zulu Love),” a celebration of the beauty of Black women, and by extension the theme of colorism, already addressed in “Vanity Slaves” by Kendrick Lamar EP.

Discrimination based on the variations of skin color within the black community, whether dark or light, remains a societal issue. At the time of slavery, certain slaves with darker skin were forced to work in the fields, while those with lighter skin, often the result of rape by white masters, were closer to the domestic sphere.

This division created tensions between the oppressed, benefiting from a kind of education and thus achieving greater social status than those who toiled in the fields. On “Complexion (A Zulu Love),” Kendrick rapped:

“Sneak me through the back window, I’m a good field nigga

I made a flower for you outta cotton just to chill with you.”

With “Complexion (A Zulu Love),"”Kendrick Lamar, assisted by the rapper Rapsody, made of the dark skin, which she clarified or deepened, a synonym for beauty, elevating the colorism to negative connotations. The track, which Kendrick didn’t want to rap, wishing to let Rapsody do two verses, before changing his mind. Prince, whose father Kendrick was a fan of and who inspires him with his way of using his voice, was planned for the chorus. "Prince had heard the track, loved it, and the concept made us discuss many things. We were sitting and talking in the studio, and as time passed, we saw that we wouldn’t record anything that day; in the end, it’s as simple as that," reveals the rapper.

It’s no coincidence, then, that “Alright” and “Complexion (A Zulu Love)” are the culmination of a path that began seven years earlier, with Kendrick Lamar’s very first steps, by simply asserting his identity. On “i” or “The Blacker The Berry,” we can guess an itinerary that the artist maps out for himself, between the need to show himself, to assert himself, and the obligation to reveal himself.

“I got the impression that I belonged in Africa,” he affirmed. “You touch things you’ve never touched before, you appreciate things harder than I’ve ever done. You realize that beauty can be beautiful, and you say it to someone who lives in music.”

Motherland

This desire took shape on “Momma,” the ninth track of To Pimp a Butterfly. To the public, to whom he says “soft[ly],” in an version without the parties vocally by Lalah Hathaway, produced in 2013 and then on cassette for an anthology released by the label Stones Throw. When shooting for the magazine Complex, Eric Coleman, friend of Kendrick, took a cassette and played it for the photographer—Kendrick Lamar. The background tells of the number of telephone call with Knxwledge, who called an hour and a half later to rework the production of TPAB.

The first two verses of “Momma” show a Kendrick at peace, taking stock of everything he has learned since the beginning of his career. “We were waiting for you, we were waiting for you,” the voices repeat in a call-and-response, like a celebration of the journey. Kendrick’s spirit is carried by this voice, coming from a man with a voice that resonates with the necessary steps to guide his path:

I know everything, I know Compton

I know street shit, I know shit that’s conscious […]

I know if I’m generous at heart, I don’t need recognition

The way I’m rewarded—well, that's God’s decision

Despite all the knowledge he thought he had accumulated, he ends his second verse by emphasizing that he knew nothing [before] coming back home.

This home is not Compton, but Africa, where during his journey, he meets a little boy who resembles the child he once was. The child assures him that despite the language barrier, they can understand each other because they come from the same place. “Take a look at your ancestors,” he asks him. “Then make a list of everything you think you’ve accomplished, step back, and realize that it’s all nothing but trivialities. You think your life is full of turmoil, you think you know yourself, but I can tell you who you really are, the boy promises. And if that scares you, then I’ll leave and let you take the plane back, but if you really want to know, I’ll show you. Once I’ve taught you everything, you’ll become a messenger, and you’ll have to tell those who stayed in Compton to come back home too.”

These words propel Kendrick into an existential crisis: in the final section of “Momma,” his voice and the beat change several times, throwing him into a confusing whirlwind, where the rapper seems to no longer know who he is or what he thought he was. He even says he feels paranoid, suicidal, and above all, lacking answers.

"People have said a lot of things about this album, called it ‘an album of a generation’ and all that stuff," he says during the Kunta Groove Sessions. “But in fact, making this album was therapy for me. The life I knew completely changed in the six months following good kid, m.A.A.d city. People were saying you’re incredible, and you try to believe that. But it’s hard because you’re a prisoner of where you come from. As I said on the Kendrick Lamar EP, I needed to be myself, damn it."

How can he find inner peace? If he doesn’t find it entirely in Africa, his journey allows him to see his life from a new angle:

“I think I’m still growing,” he explains to comedian Dave Chappelle in 2017 via Interview Magazine. “The more people I meet, the more cultures I start to embrace, the more people I open myself up to—it’s a growing process I’m excited about. But it’s also a challenge for me, to be at this level and still be able to connect with somebody who’s living that everyday life. At first it was something I struggled with, because everything was moving so fast. I didn’t know how to digest it. The best thing I did was go back to the city of Compton, to touch the people who I grew up with and tell them the stories of the people I met around the world. Making To Pimp a Butterfly was me navigating those experiences. I went to Africa and I was like, ‘This is something I can enjoy and something I can challenge myself with.’”

Compton (Is) Africa

To celebrate this return to the Earth, Kendrick Lamar incorporates certain elements into “Momma,” but also taps into the power of images. First example: the pocket of the single “The Blacker the Berry” features Black babies holding the hands of a woman, Black herself, symbolizing the African continent, from which these babies draw the necessary energy to grow.

More explicitly, the rapper’s performance at the 2016 Grammy Awards places Africa at the center of the debate. In collaboration with Dianne Garcia, stylist for Kendrick Lamar and SZA, and designer of the TDE-branded clothing, she plays a key role behind the collection created for the release of the album To Pimp a Butterfly. Dave Free and Kendrick collaborate to conceptualize the concert a month before the ceremony. They discuss the concept, brainstorm costumes, and plan the sequence of performances. Dianne is then tasked with bringing their vision to life.

If the performance stands out for its succession of various ambiances, its colors, the fire that burns, and the messages it carries with an intensity that, four months after the release of TPAB, K-Dot raps “The Blacker the Berry” and “Alright,” it’s in the details that the most striking symbols are found.

The costumes of the dancers in the background were painted with UV motifs. These become visible as the lights change: one discovers forms reminiscent of the Ethiopian tribes of the Surma and Mursi. On their backs, numbers evoke the date of Nat Turner’s revolt (August 21-23, 1831). The dancers take the stage during the section dedicated to “Alright,” wearing necklaces similar to those worn by women of the Maasai tribe, present in Kenya and Tanzania, and are covered in red paint inspired by the tribe Himba from northern Namibia—the red color represents blood and the earth.

“We chose this tribe because within it, it’s the women who do all the manual labor while taking care of their homes, while the men tend to the herds and discuss politics,” reveals Dianne Garcia.

The end of the rapper’s performance pays even greater homage to Africa. The shape of the African continent appears in the background, and the name “Compton” is then inscribed at its center, linking Kendrick Lamar’s hometown to everything he has learned during his journey on the land of his ancestors, showing that Compton and Africa are now integral parts of his identity. And of America’s.

If Kendrick draws inspiration from the encounters he makes in South Africa and expresses them in his music and on stage, it’s a man he never meets, but whose aura permeates every square meter of the country, who inspires him the most: Nelson Mandela.

“Bring some of this story back to your community.”

One visit particularly impacts Kendrick: the cell where Mandela was imprisoned on Robben Island, where opponents of the apartheid regime in South Africa were confined between 1948 and June 30, 1991, the date of its abolition. Nelson Mandela was sent there in 1964 and remained imprisoned for eighteen years.

The rapper is inspired by the philosophy of ubuntu adopted by Nelson Mandela, traces of which can be found in To Pimp a Butterfly. In sub-Saharan Africa, this philosophy promotes the respect for one’s neighbor, compassion, and mutual aid. Nelson Mandela describes it in these terms:

"It’s a universal truth, a way of life, which raises the question of an open society. […] When a traveler arrived in a village, its inhabitants immediately offered him food. They showed attention, respect, and altruism. […] The question is the following: will you do something to improve our societies?"

Guided by these principles, and despite his isolation on Robben Island, Mandela continued to influence those who fought against the racist apartheid regime. The flame of revolt still burned within him, and he remained optimistic about the future. In a letter sent to his family in 1969, he wrote:

“I don’t know when I’ll return home, my loves. But don’t worry about me. I’m happy, I’m doing well, and I’m full of strength and hope.”

On Robben Island, Kendrick gazes at the walls of Nelson Mandela’s cell, sits where he slept, and realizes how small it is and how confined his spirit must have felt.

“It brought me back to reality,” affirms Kendrick. “We saw the stones they had to dig up every day as punishment. I could feel the spirits of the prisoners telling me: ‘Bring some of this history back to your community.’ That’s exactly what I did.”

After his visit, Kendrick wonders how it’s possible not to lose one’s mind in such a context, and above all, by what means Mandela managed to remain the leader his people had chosen.

“I want you to love me like Nelson.”

These questions are the basis of “Mortal Man,” a song in which Kendrick Lamar does not place himself in the line of Nelson Mandela, Malcolm X or Martin Luther King, the three men that he also cites, but rather wonders if he will one day be able to live up to them.

“I’ve felt that pressure in Compton, looking at the responsibility I have over these kids,” he told Billboard magazine in 2016. “The world started turning into a place where—where so many were getting no justice. You got to step up to the plate. On ‘Mortal Man,’ I don’t say: ‘I can be your hero.’ I rather wonder if you really think I can be.”

Kendrick praises Nelson Mandela’s ability to forgive and advocate peace even after his prison sentence. Aware that he will inevitably make mistakes, he wonders what his audience will think of him if he were to disappoint them. Would he forget him, would he denigrate him, as he denigrated Michael Jackson after he was accused of pedophilia? Would he be killed like Malcolm X, murdered by supporters of a group of which he had been the leader? What would happen if the government trapped him, putting cocaine in his car for example: would he be reduced to an accrc

What would happen if the government trapped him, putting cocaine in his car for example: would he be reduced to a drug addict, despite everything he has accomplished? Kendrick asks for mercy towards him:

“As I lead this army, make room for mistakes and depression,” he pleads.

Despite everything he learns about himself in South Africa, “Mortal Man” raises more questions than it provides answers, a constant in Kendrick Lamar’s career.

“What I love most about ‘Mortal Man’ is the way the song arrives, right after ‘i’. In ‘i’, I put my leadership forward. […] And then you have ‘Mortal Man’ where I question that same leadership. It’s me asking myself questions. I can make a track like ‘i’, but will my friends, for whom I rap it, even listen?”

Rapping under an alter ego rather than his real name allows Kendrick Lamar, by distancing himself from his own identity, to leave behind that feeling of insecurity. K-Dot was convinced he was the fiercest and most talented rapper on the planet—before K-Dot, he rapped under the names Volcano or K-Mac—and Kung-Fu Kenny is a martial arts master who has reached the peak of his technique.

Later, on the first track of the original soundtrack inspired by the film Black Panther, released on February 9, 2018, less than a year after DAMN., Kendrick Lamar chooses to embody another character, fictional this time. He presents himself as a courageous and charismatic king, a leader without fear or rival at his height.

“Because the king don’t cry, king don’t die/King don’t lie, king give heart, king get by, king don’t fall/Kingdom come, when I come, you know why/King! King! King! King!/I am T’Challa!,” he proclaims.

The Favorite of His Peers

Before Black Panther: The Album or DAMN., Section.80 was his launchpad into a certain underground market; good kid, m.A.A.d city ushered Kendrick into the upper echelons of rap and was repeatedly validated by millions of examples, but it was already a text for posterity. A moment when he became the icon of a generation.

To Pimp a Butterfly was certainly propelled by “King Kunta” and “Alright,” but it didn’t really produce another hit, aside from perhaps “These Walls,” which was rather R&B. In reality, the whole album established itself as a must-have on the rap scene, and sold over a million—and some—copies. But it was mostly streaming that exploded, nearly breaking records.

And it became ingrained, so much so that Barack Obama invited Kendrick Lamar to the White House and named “How Much a Dollar Cost?” as his favorite song of 2015, a political gesture. The strongman of the United States was sending a signal: rappers, Motown singers, Aretha Franklin, John Legend, or even Marvin Gaye, A Love Supreme by Coltrane, or “A Change Is Gonna Come” by Sam Cooke—seeing that Pharrell, who participated in “Alright,” is like the continuation of a story.

That LeBron James identified with “i” and then picked up Toni Morrison from good kid, m.A.A.d city, one of the greatest writers of our time? So, in terms of popularity and engagement, everything was there.

All that would change on his fourth solo album—an album released in April 2017, when DAMN. snippets made Kendrick stand out more as a producer working with R&B artists, having endorsed a calmer 2015 by remixing for Taylor Swift on “Bad Blood,” ultimately conquering his so-called enemy.