Guru’s Strategy, Repeating Expansion and Convergence

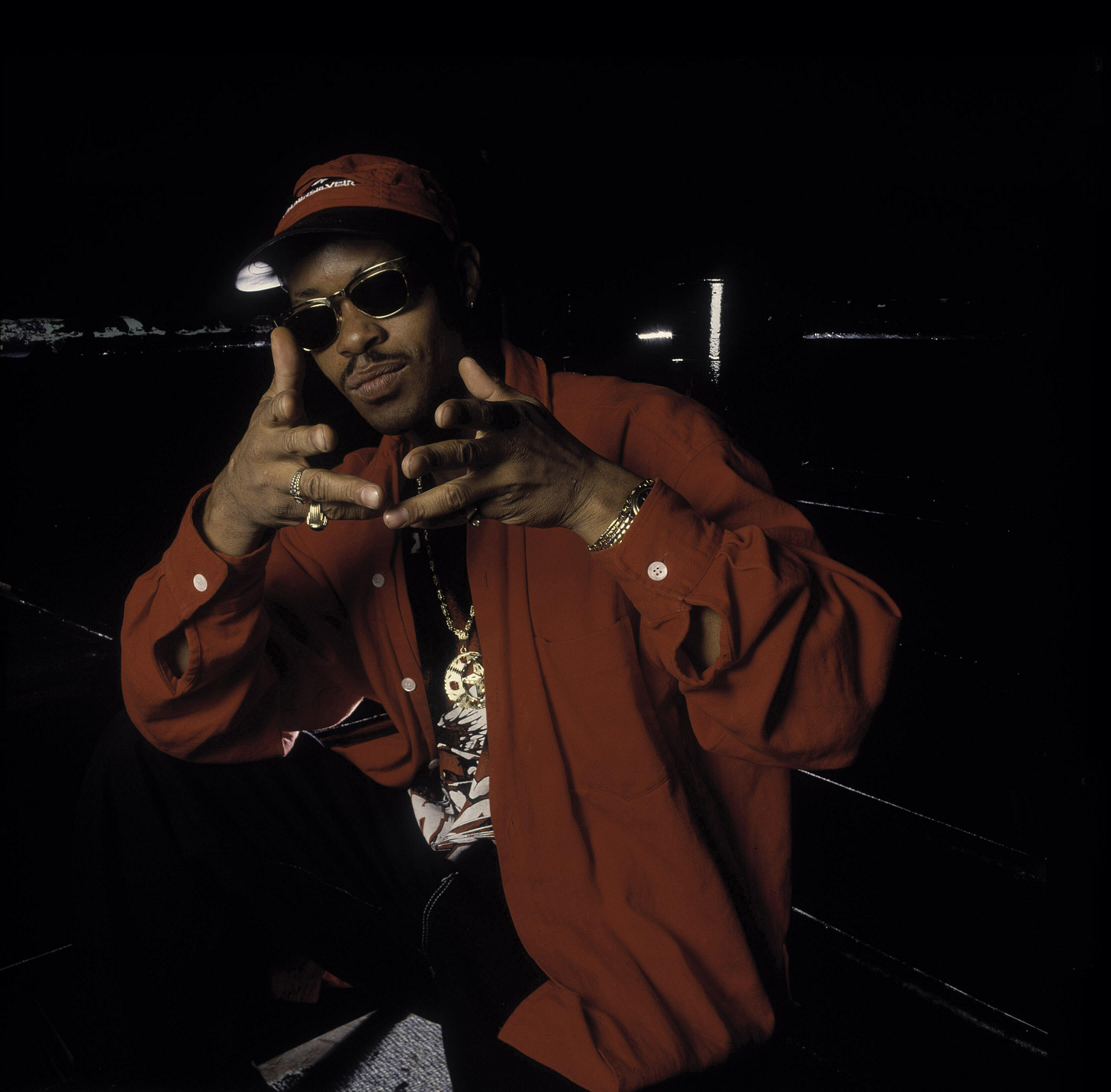

Guru says that the new Gang Starr album, to be released next year (1994), will be more hardcore. What drove him to create the controversial work Jazzmatazz?

Interview by: Shiro Sasaki

This conversation is translated, lightly edited for content and clarity, follows below.

All of a sudden, it feels like we’ve returned to the mood of the “MZA days” at the beginning, and the American contingent of rap artists seems to be heating up. Before this, reggae and such had also been quite vibrant, and the range of artists was fairly diverse. But starting with the August 25 Jazz Cafe Tokyo (*)—where A Tribe Called Quest and Alice in Chains ended up interacting on the same stage—there has been a flurry of activity for roughly the past six months: Cypress Hill & “Account Business?” & “Aunt Business?” (unclear), De La Soul, Main Source, De La Naty… and more have come to Japan; plus, acts originally slated to come—D. Klan, Brandy Mace, Run, DMC, and Tatch—were able to continue their shows… so in any case, the movement continues. It’s an encouraging development (whether it’s profitable economically is another matter).

The Jazzmatazz crew, who came along with Guru, were also involved in that timing and came to Japan. You might expect them to have continued their visit because of the new album and the chance to see Cypress at the same time, but it appears that a good amount of coincidence was at play. The fact that they experienced a live show in Japan out of curiosity was also a kind of encounter, and apparently Shibuya On Air on September 10 was nearly full. Even with hardly any B-boys present—apart from “people in the business”—it seems that amazingly enough there was no sense of incongruity at all. Strangely, in Tokyo, it seems that jazz-fan–looking audience members took their places naturally right up in the front row. It appears that B-boys are still not showing up in those thumping dance-floor spaces around town.

By the way, what Guru made for this Jazzmatazz project this time (or what he demonstrated, you could say) goes beyond the realm of a mere “experimental technique”; I, for one, get the sense that it contains some earnest message. In other words, the concept of this project—brought to completion by assembling that family—is fundamentally a “new personal attempt.” It’s not as though, by changing modes, he’s throwing out what Gang Starr has done so far; nor is he being complacent with what he’s achieved so far. Rather, it seems best to regard Guru as this total creative force.

Well, anyway, what kind of image has attached itself to Gang Starr as a result of interviews surrounding this album? From my perspective, if a person has taken in this one record, Jazzmatazz, maybe they’ll think, over lunch, “Ah, it’s hard, but it’s got innocence. I’ll stick with Gang Starr.” And according to Guru, the new Gang Starr album, their fourth (Hard to Earn), to be released next year, is going to be more hardcore in content. On the other hand, he’s also trying to move the image in the direction of “This is hardcore jazz-funk,” and that gap is part of who he is. Underneath that, it seems, is the way he works creatively, as well as hopes for how DJ Premier might evolve. Perhaps they can raise this new album one more level?

“There’s this idea that Pete Rock, Q-Tip, Premier, and those guys represent one of the classic New York styles, but I think they need to keep moving that concept forward. One guy’s working the samples, or one guy’s the DJ stylizing the sound, or there are all sorts of setups. It takes a huge amount of time to put together a full album, up to the point where the sound is complete and sealed into the record. At least three tracks in there…they’re all heavy on the bass line or the beat.”

Those production pieces by Guru included on the soundtracks of Boyz II Hood and Menace II Society—that strawberry “Sparlock sample”—are a quintessential hardcore rap sound, fit to be called a hip-hop anthem.

“What’s significant for me is the contrast with that track. While ‘Jazzmatazz’ is coming out, I figure that underground still knows how to break out of the underground scene, right? Sound-wise, that’s good in its own right. Cut & Slow made this sleazy funk.

While building up that kind of impact, I’m not feeling inferior about being ‘underground.’ On the flip side of that, I also put a lot of energy into activities carried out on a fully underground level.”

“We put out a single through Gang Starr Productions, and through my own pen-pen… venture label—yeah, about 3,000 cassettes and 5,000 records are in circulation—and of those, maybe 50. One of those jazzy, hard-edged tracks got worldwide recognition, and in the end I got an offer and signed. The previous track was signed in Holland. Premier’s beats were dope, and when you mixed in the sound of dripping water, it made it all the more refined (sings a bit), and even now the A&R people say they couldn’t wait for eternity. It’s enough that I now think, ‘Man, I should have just put that (record) out myself.’ It sold 60 or 70 thousand copies, with Big Genemas rapping alongside. There are still things about EPMD’s relationship with Premier that even now aren’t so clear.

Over the long span of that ‘producers’ work’ we did before, I realized that Premier’s personality is indeed that of a craftsman. We might joke around like, ‘Hey, Premier, didn’t you say you could’ve made that beat first the other day?’ and laugh it off (laughs). But Premier is skillful. He moves smoothly through the process of recording with turntables, samplers, and MTR. He did whatever he wanted with a few machines—SP1200, MPC60. Meanwhile, Guru would be in the studio the whole time polishing his MC performance, and the engineer would have nothing to do, so he’d be in another room playing billiards (laughs). In my case, I’d tell the engineer, ‘Sample this part of this record and finish it like this,’ and then he’d do it for me, sort of like that.

“Now that you mention it, there was a time like this: regarding three songs I made for the new Gang Starr album, once I’d done the sampling stage, I just handed the tapes over to Premier to see what would happen, and he’d say, ‘All right, cool’… if he didn’t hate it or didn’t think it was a no-go. Then we’d add certain elements of ‘this approach to the beat,’ or I’d ask him for a certain sound from ‘this part of that record,’ or I’d have him check my opinions on the mix. The back-and-forth is more frequent now than ever before.

For instance, there have been times when Public Enemy or KRS have asked me to produce for them. They’d be like, ‘Let me do that too,’ and I’d say, ‘Me too.’ Then they’d go, ‘Well, maybe you can do a track on my album…’ That’s not a typical occurrence for me. I did a remix of a sound single… which meant more opportunities for me to be involved in the market (I was happy about that). But still, it basically means that what I wanted to communicate—my own consciousness—ends up on the record (laughs). Oh yeah, there was also a time I had to finalize some cut & re-bounce (laughs). People say that piece is tricky to cut & re-bounce. As a producer continuing my own career, I try to stay positive even if it takes me a few years. Well, I’m still looking for more tracks, so it’s got to be Premier again. I might decide next time on something “like Jazzmatazz” right on the spot.

In short, you might suspect Guru carried some sort of complex about Premier over on the American side… but in reality, he’s not fixated on those sorts of words; rather, there’s apparently a sense of respect for Mia’s ‘visitas.’ Well, you know, if they say “Just use this part of the tape” and hand it to me, I’ll play it (laughs). If he doesn’t say it himself but comes in on the conversation anyway… the engineer will say stuff like, ‘This record is that one, right?’ or whenever it’s no good: ‘Roooong… no, that won’t work.’ He’s the strong, silent type, anyway.

After that, through a friend, he was like, ‘Hey, so that was released, huh? Then I’d like to tour Jazzmatazz,’ so he came to Mountain Stage and sang for me, and he said he liked “Lounge to Trust Me.”

The real highlights are the collaborations and interactions with other artists involved in Jazzmatazz. In particular, American domestic labels often overlook how we approach cooperation. The best method for negotiating well with artists is something like Jazzmatazz. It extends from MC → ground-level expansions, but there are times when Japan’s DJ Klan must also join in on an album of flora and fauna with rap in a spirit of camaraderie.

‘My style isn’t just one. My style is this “voice.” That doesn’t mean there’s only one style. I also don’t think there’s only one style around. I can create my own style. The only rapper I consider worthy of that name is KRS-One.’